I was living in London when I started reading the old Irish stories again. I had gone there for work and had started missing home pretty hard. It’s a common thing for expats to try to reclaim a little of their identity by tuning into the radio for familiar accents, or listening to the bands making their name back in Whelan’s. I did both anyhow.

When I mentioned I was reading the old stories again, people would invariably ask me to tell one. This could be in a pub, in a friend’s flat late at night, on a park bench. I was working at a small design company at the edge of Soho. I was working mainly on code, which I hated, being a designer, and was finding myself a little out of place in the city.

The work was pretty intensive but the people were unusually friendly and at lunchtimes some of us might venture down to a pretty little park just off Tottenham Court Road and take our sandwich in the sunshine. They were from all over, South Africa, New Zealand, Pakistan, Slovenia, and they all took a particular interest in my book of stories. They all missed their homes the same way.

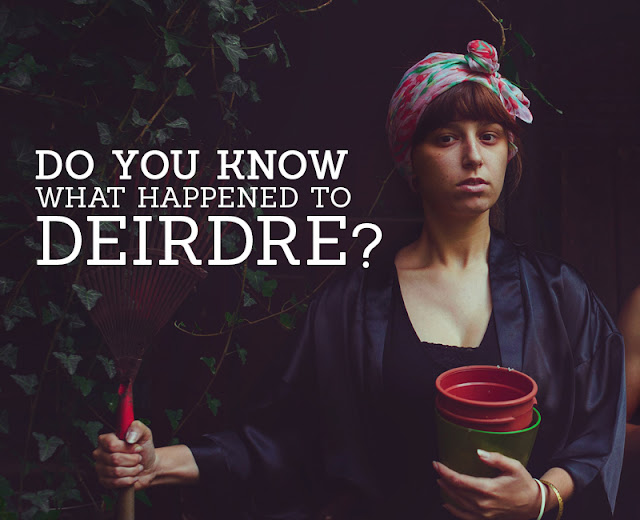

The story which came to me the easiest and I told the best each time was Deirdre of the Sorrows. Probably because it’s so evocative of so many other tales: Rapunzel, Sleeping Beauty, practically any story where there’s a damsel rescused by a young prince, only in the Irish version Deirdre is no mere damsel, she’s not rescued by any prince and it certainly doesn’t end happily.

Maybe it was the finale that made me enjoy the telling of it. How people would recoil, shocked. How they’d comment on the bleak Irish outlook.

There was that moment of silence after the end of it, in the sunshine, with the bees hovering by our half-eaten salad rolls. People were waiting to be told everything was going to work out. Perhaps it was this which inspired me to take the story and place it in today’s Ireland, which hasn’t seemed quite as bleak in quite a time.

I wanted to write a thriller, I wanted it to talk about the country today, the issues at hand, but I wanted it to remain faithful to the strangeness and shock of the original. For this reason I had the story told by a Puca, a supernatural creature from mythic tales, who speaks coarsely but objectively.

The story of Deirdre tells of a very young girl promised to the high king, Conchobor, who raises her from infancy to be his wife. Deirdre runs away from the king having met a young man and the king chases the couple, along with his brothers, as far as Scotland. He promises them safe passage home only to murder all the young men when they get there. The king then asks of Deirdre who it is she hates most in the world and she answers Fergus, the man who killed her beloved. He tells her that the punishment for her flight will be that he will share her with Fergus. Her reaction to this, and the end of the tale, comes when she’s riding in a chariot with both men and raises her head in sight of a low hanging rock , so that she’s decapitated.

The story deals with youth, in particular the mistreatment of the young, power, property and oppression. These are ordinary enough themes, but seem especially relevant in the Ireland of 2014. It’s relevant enough that another writer, Eamon Carr, was publishing another modern retelling of it, Deirdre Unforgiven, with the Doire Press at the same time I was with Creativia. His version is in verse and uses Deirdre to convey his outlook on the Troubles.

More interesting again is how these two reinventions are actually just the tip of the iceberg. People are retelling the old stories over and over in newer and more diverse ways. Last year Will Sliney wrote and illustrated Celtic Warrior: The Legend of Cú Chulainn, a graphic novel telling the story of the Táin Bó Cúailnge for a young generation. This followed on the heels of previous publications like Brian Boru: Ireland’s Warrior King by Damien Goodfellow and Tomm Moore’s Oscar-nominatedSecret of Kells, An Táin by Colmán Ó Raghallaigh and Róisín Dubh by Rob Curley and Maura McHugh.

There’s a sense that this isn’t simply a rehash of the leprechaun museum or twee Temple Bar bodhráns reeling in the tourist pennies, but that people are telling the stories as a part of who they are, the same way I was in the park, or when a few visiting friends from home in Greystones and I tried patching together the story of Oisin and Tir na nOg on the last Tube home to Bayswater to the bemusement of an otherwise sober carriage.

These stories were crafted over centuries by master storytellers. They come laden with historical and cultural significance and work as a touchstone for something real, a foundation speaking to us about ourselves whereas so much of modern storytelling, in whichever form, comes over as purely commercially driven or as a mere lightweight escape.

After I had finished in the park that day, Amir, who was from Pakistan, told a tale from his own culture. I don’t want to give the impression here that we habitually sat in circles on the grass, singing one another the songs of our people. These were guys who spent hours arguing over why Aaron Lennon wouldn’t ever make it into the Spurs first team or rating girls in the park out of 10 (I know).

We were by no means cultural attachés, but that particular lunchtime something struck which left us feeling a little closer to one another and nourished for the experience. Amir told the story of Heer and Ranjha. It’s a Punjabi tale, from his district, and is one of the world’s most famous and tragic love stories. Naturally I was too ignorant to ever have heard of it. In fact, none of us had. He told it fantastically. It’s about young lovers kept apart by a powerful, jealous rival, and it ends just as tragically as Deirdre. It’s well worth looking up online. Heer and Ranjha was remade as a film called Rockstar a couple of years ago in Bollywood.

Mythology and folklore are enjoying a resurgance internationally also. Guy Ritchie has just been taken on to direct a series of King Arthur movies. Television shows like Once Upon a Time and Grimm are reimagining the familiar fairytales of Europe in modern, urban settings. The latest series of Percy Jackson books from Rick Riordan tell tales from Greek mythology from the point of view of Percy. Zeus Grants Stupid Wishes by Cory O’Brien, which retells myths in casual online IM speak, became an Amazon bestseller (his website is well worth checking out incidentally: bettermyths.com – even though he doesn’t have any Irish ones on there). I watched an episode of Supernaturalrecently which featured changelings, a staple of old Irish fairy stories, as wicked mother-eating monsters. I won’t even talk about Thor and Loki.

There might be a strong smack of fan-fiction to all of this. Tapping a cultural heritage already very familiar feels quite like standing on the shoulders of giants. It certainly felt that way to me when I wrote It’s The Stars Will Be Our Lamps. At the same time I don’t happen to think it’s all that far from people sat around fires listening to the storyteller down the centuries. The good stories stick around and they always will in some or other form. It’s up to us to find new ways to tell them.

This article was originally published in The Irish Times website

If you're interested in Irish mythology, maybe you'll like my novel, Sour, which retells an old Irish myth as a modern murder story: